Something to look forward to: Two of the world's wealthiest men are racing to tackle a challenge that could transform human space travel: refueling spacecraft in orbit. Solving this problem could dramatically expand the reach of missions beyond Earth, opening possibilities for longer journeys to the moon, Mars, and potentially even deeper into the solar system.

Elon Musk's SpaceX and Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin are separately developing systems that would allow rockets to refuel once they've left Earth, a concept sometimes described as a "cosmic truck stop." Engineers first proposed orbital refueling as early as the 1960s, before NASA even sent astronauts to the lunar surface, but only now are private companies putting the idea at the core of their deep-space strategies.

Fuel has always been the central constraint for launching heavy spacecraft. NASA's Apollo program underscored the limits. The Saturn V rocket that carried astronauts to the lunar surface in the late 1960s weighed 6.5 million pounds at liftoff. About 5.5 million pounds of that total weight was fuel.

By launching with less fuel and replenishing in low-Earth orbit, companies believe they can send larger payloads or additional crew deeper into space. Dallas Bienhoff, a veteran of in-space fueling studies at Boeing who now works with robotic-mining firm OffWorld, told The Wall Street Journal this approach could also lower costs when paired with reusable launch vehicles, which are already reshaping the economics of rocketry.

"It has got to be done," Bienhoff said. "Otherwise, we're going to be limited with what we can achieve in space."

The central technical hurdle remains handling the propellants themselves. SpaceX and Blue Origin plan to use liquid fuels that require extremely low temperatures. In the vacuum of space, they naturally tend to warm and boil off, making the challenge less about storage tanks than refrigeration systems that function reliably in microgravity. Blue Origin CEO Dave Limp said in July that the company had made significant progress on hardware designed to prevent boil-off. However, engineers caution that managing cryogenic liquids in orbit can involve unpredictable behavior.

Even moving the fuel presents challenges. In microgravity, liquids no longer settle predictably in tanks, explained William Notardonato, chief executive of Eta Space, which is testing fluid management on satellites.

"You don't know where your liquid is stored," he said. "The propellant might be up at the top of the tank."

SpaceX has conducted initial experiments with in-orbit fuel transfers. In 2024, the company tested moving fluids inside a Starship vehicle and said its next step is to attempt propellant transfer between two separate spacecraft. Starship delays, including an explosion during a ground test in Texas last year, have slowed those plans.

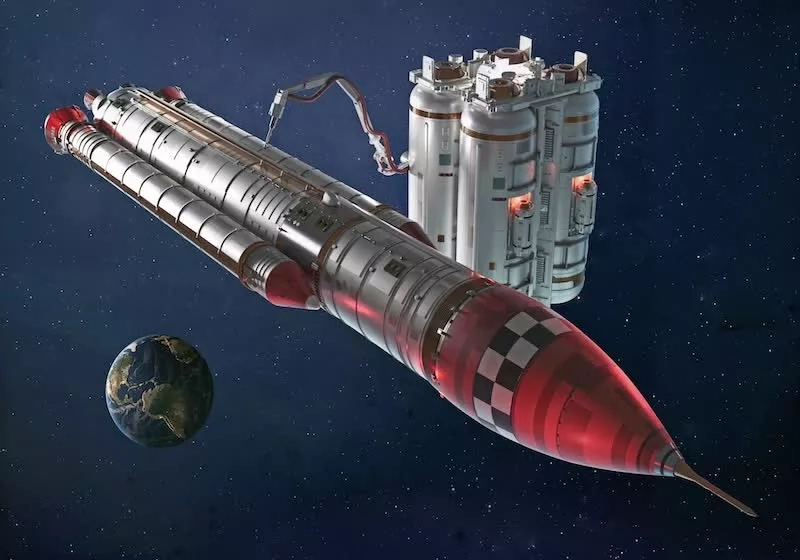

The company's model for NASA's Artemis lunar program relies on repeated tanker flights. A Starship would serve as a depot in low-Earth orbit and take on fuel through multiple missions of dedicated tanker variants. A lunar lander Starship would then dock with the depot, refuel, and proceed to the moon with crew on board. How many launches a single mission would require remains uncertain. However, current and former industry officials have projected figures ranging from 10 to 40 flights.

Blue Origin has set out a different approach. Its system centers on a "transporter" vehicle launched on the company's new heavy-lift rocket, New Glenn, which flew for the first time in January. The transporter would take on fuel in Earth orbit, carry it to lunar orbit, and use it to prepare a separate lander for the crew arriving on another ship. Company officials have so far avoided specifying how many refueling flights such a mission might require, though NASA has begun evaluating the approach under its Artemis planning.

The physics and logistics have left some space-industry veterans skeptical that orbital refueling will be ready in time to meet NASA's crewed lunar-landing schedules. Nonetheless, both companies are pressing ahead.

Slight chance of Starship flight to Mars crewed by Optimus in Nov/Dec next year. A lot needs to go right for that. More likely, first flight without humans in ~3.5 years, next flight ~5.5 years with humans.

Mars city self-sustaining in 20 to 30 years.